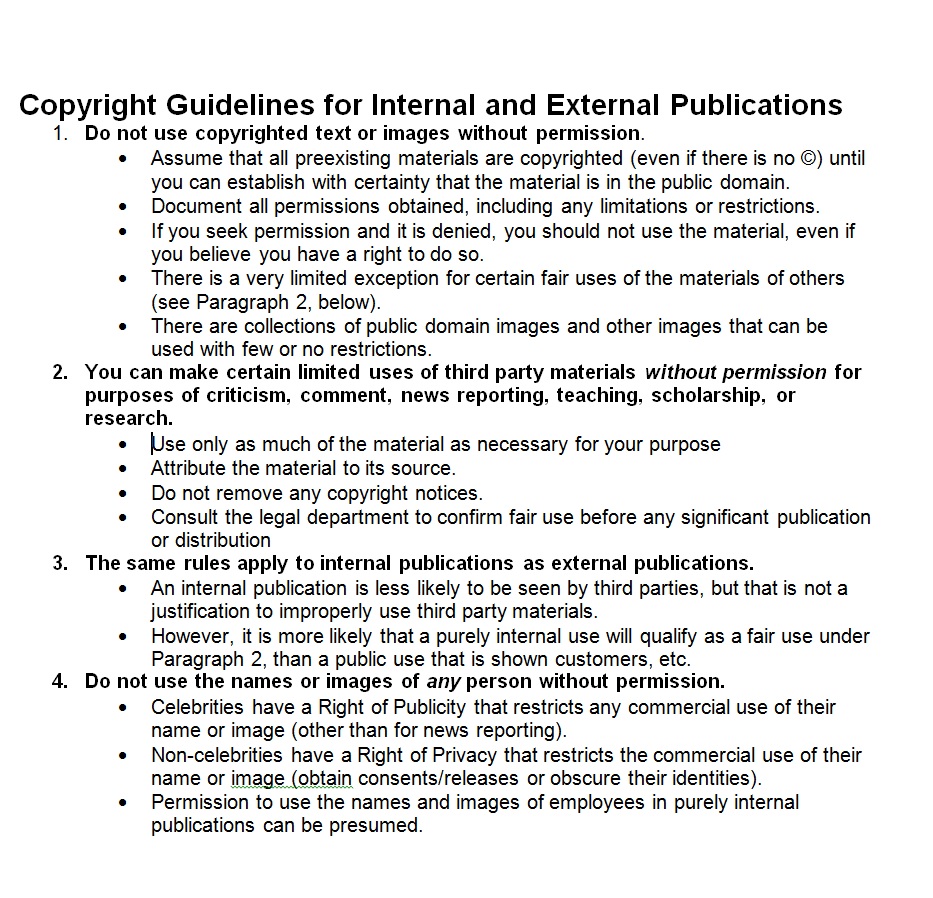

The Supreme Court finally resolved the dispute between Google and Oracle over Google’s copying of 11,500 lines of declaring code from nearly 3 million lines of code from Sun Java API was copyright infringement. Dodging the question of whether such code is even copyrightable, the Supreme Court fount that the copying of the code, for the purpose of making Android programming similar to other Java programming was a fair use.

The Supreme Court found that the Federal Circuit correctly identified Fair Use as a mixed question of law and fact, but ultimately held that the Federal Circuit was wrong as a matter of law when it reversed the jury’s determination of fair use. The Court thoroughly analyzed the four factors identified in 17 USC 107 before concluding that on balance, accounting for the functional nature of computer software, Google’s use was a non-infringing fair use.

The Nature of the Copyrighted Work

The Supreme Court said that the technology at issue had three essential parts: First, the API includes “implementing code,” which actually instructs the computer on the steps to follow to carry out each task. [Google wrote its own implementing code]. Second, the Sun Java API associates a particular command, called a “method call,” with the calling up of each task. [Oracle did not argue that the use of these commands by programmers itself violates its copyrights.] Third, the Sun Java API contains computer code that will associate the writing of a method call with particular “places” in the computer that contain the needed implementing code. This is the declaring code that Google copied.

The declaring code is inextricably boundup with the use of specific commands known to programmers as “method calls” that Oracle did not contest, and it is also boundup with the implementing code, which Google did not copy. The Court noted that the declaring code (inseparable from the programmer’s method calls) embodies a different kind of creativity. Sun Java’s creators tried to find declaring code names that would prove intuitively easy to remember to attract programmers who would learn the system, help to develop it further, and prove reluctant to use another. The declaring code was designed and organized in a way that is intuitive and understandable to developers so that they can invoke it.

These considerations meant that, as part of a user interface, the declaring code differs from the mine run of computer programs. Like other computer programs, it is functional in nature. But unlike many other programs, its use is inherently bound together with uncopyrightable ideas (general task division and organization) and new creative expression (Android’s implementing code). Unlike many other programs, its value in significant part derives from the value that those who do not hold copyrights, namely, computer programmers, invest of their own time and effort to learn the API’s system. And unlike many other programs, its value lies in its efforts to encourage programmers to learn and to use that system so that they will use(and continue to use) Sun-related implementing programs that Google did not copy. The Court concluded that in its view the declaring code is, if copyrightable at all, further than are most computer programs (such as the implementing code) from the core of copyright.

The Purpose and Character of the Use

In the context of fair use, the Court noted that it has considered whether the copier’s use adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the copyrighted work with new expression, meaning or message, i.e. whether it is transformative. In determining whether a use is transformative, the court said that one we must go further and examine the copying’s more specifically described purposes and character.

The Court said that Google’s new product offers programmers a highly creative and innovative tool for a smartphone environment. To the extent that Google used parts of the Sun Java API to create a new platform that could be readily used by programmers, its use was consistent with that creative progress that is the basic Constitutional objective of copyright itself. The Court found that Google copied the API (which Sun created for use in desktop and laptop computers) only insofar as needed to include tasks that would be useful in smartphone programs, and it did so only insofar as needed to allow programmers to call upon those tasks without discarding a portion of a familiar programming language and learning a new one. These and related facts convinced the Court that the “purpose and character” of Google’s copying was transformative—to the point where this factor also weighed in favor of a finding of fair use.

Even though Google’s use was a commercial endeavor — this was not dispositive, particularly in light of the inherently transformative role that the reimplementation played in the new Android system. The Court also questioned whether bad faith has any role in a fair use analysis, but in the end simply concluded that it was not determinative in the present case.

The Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Used

While when considered in isolation, the quantitative amount of what Google copied was large — totaling approximately 11,500 lines of code, considering the entire set of software material in the Sun Java API, the quantitative amount copied was small. The total set of Sun Java API computer code, including implementing code, amounted to 2.86 million lines, of which the copied 11,500 lines were only 0.4 percent. While even a small amount of copying may fall outside of the scope of fair use where the excerpt copied consists of the “heart” of the original work’s creative expression, copying a larger amount of material can fall within the scope of fair use where the material copied captures little of the material’s creative expression or is central to the copier’s valid purpose.

The Court said that a better way to look at the numbers was to take into account the several million lines that Google did not copy. The Sun Java API is inseparably bound to those task-implementing lines — its purpose is to call them up. The code Google copied was “not because of their creativity, their beauty, or even (in a sense) because of their purpose.” Google copied them because programmers had already learned to work with the Sun Java API’s system, and it would have been difficult, perhaps prohibitively so, to attract programmers to build its Android smartphone system without them. Further, Google’s basic purpose was to create a different task-related system for a different computing environment (smartphones vs. desktop and laptop computers) and to create a platform—theAndroid platform—that would help achieve and popularize that objective. The Court concluded that the “substantiality” factor will generally weigh in favor of fair use where, as here, the amount of copying was tethered to a valid, and transformative, purpose.

Market Effects

The Court acknowledged that consideration of market effects where computer programs are at issue can be complex. Potential loss of revenue is one consideration, but not the whole story. The courts must also take into account the public benefits the copying will likely produce. The Court noted that the jury could have found that Android did not harm the actual or potential markets for Java SE. The jury was repeatedly told that devices using Google’s Android platform were different in kind from those that licensed Sun’s technology. The Court found that taken together, the evidence showed that Sun’s mobile phone business was declining, while the market increasingly demanded a new form of smartphone technology that Sun was never able to offer.

The Court said that a substantial part of the value may come from the fact that users, including programmers, are simply used to it, and there was no indication that the Copyright Act sought to protect third parties’ investment in learning how to operate a created work. The Court said that allowing protection of Sun Java API’s declaring code was a lock limiting the future creativity of new programs, and that this lock would interfere with, not further, copyright’s basic creativity objectives.

Conclusion

The Court held that where Google reimplemented a user interface, taking only what was needed to allow users to put their accrued talents to work in a new and transformative program, Google’s copying of the Sun Java API was a fair use of that material as a matter of law.