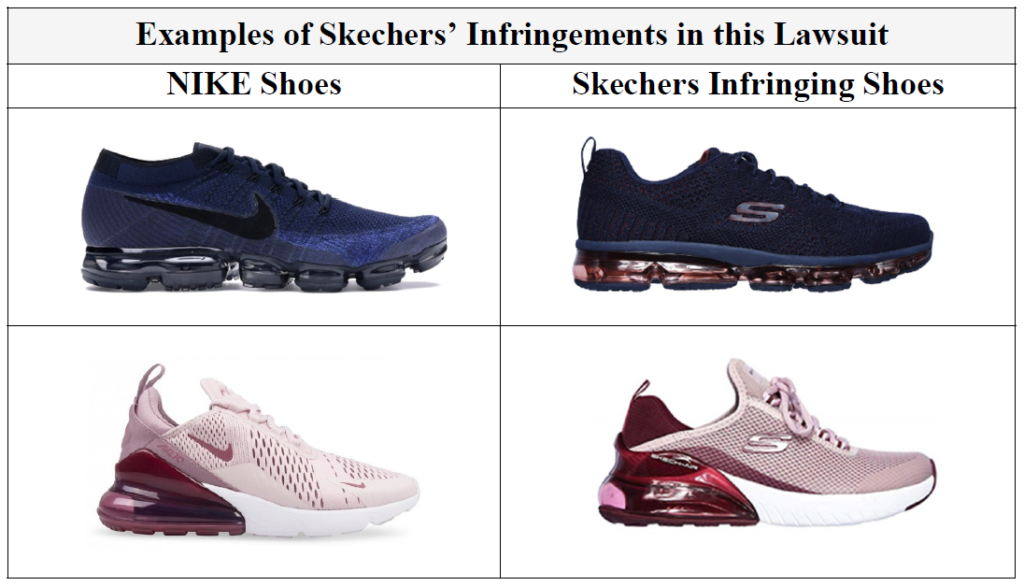

Nike recently sued Skechers for infringement of twelve of Nike’s design patents. The Complaint convincingly establishes the similarity of the appearance of the shoes:

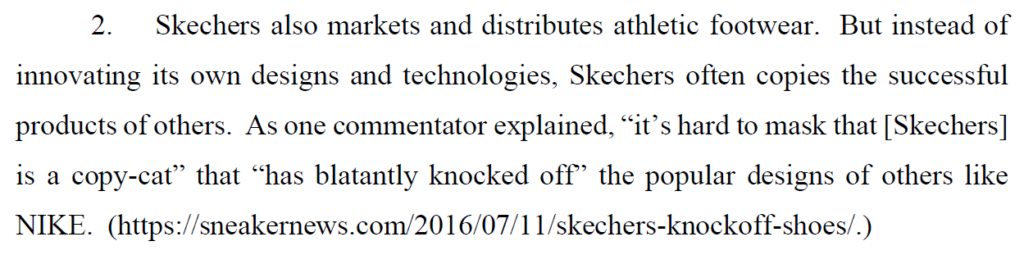

In addition to appearance, the Complaint also develops a convincing case on appearances, detailing Sketchers strategy of copying:

Nike explains Skecher’s practice of Skecherizing competitor’s designs:

Nike’s Complaint recognizes that while competition is legitimate, people inately believe that copying is wrong. While Skechers appears to embrace its conduct, most business work to preserve its image as a legitimate competitor, and not merely a copier. To this end, a business should pay attention to how it characterizes its own conduct. Internal project names that make the business look like a pirate, or internal communications that talk about “ripping off, “knocking off,” or even “copying,” can cast the company in a bad light to a judge or jury. If what the business is doing is legimate, there is no need to characterize the conduct as improper or inappropriate — when the issue is design patent infringement, appearances can matter just as much as appearance.