In Cariou v. Prince, 714 F3d 694 [106 USPQ2d 1497] (2d Cir. 2013), the Second Circuit said that a use of a copyrighted work need not comment on the original artist or work, or on popular culture, in order to constitute “transformative” use that qualifies for fair-use defense. All that is needed to qualify as a fair use, is that the new work alters the original with “new expression, meaning, or message. Thus the Second Circuit reversed the district court judgment that Cariou’s photograph (left) was infringed by Prince’s “transformative” image (right).

Apparently intent on testing the lower limits of “transformation,” Richard Prince has continued with his appropriation style of artistry, and has been sued by two other photographers:

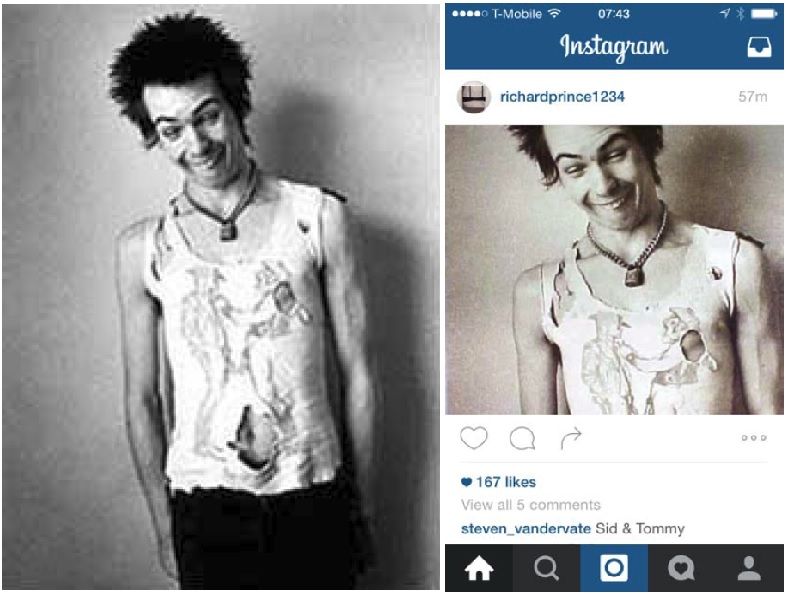

In Graham v. Prince et al, [1:15-cv-10160-SHS ] filed in the Southern District of New York on December 30, 2015, Graham complained about the reproduction of his photograph with a instragram-style border:

In Morris v. Prince et al., [2:16-cv-03924-RGK-PJW ] filed in the Central District of California on June 3, 2016, photograph Dennis Morris complained about the appropriation of a portrait he published in a book by Richard Prince:

In Salazar v. Prince et al., [2:16-cv-04282-MWF-FFM] filed in the Central District of California on June 15, 2016, model/makeup artist Ashley Salazar complained about the appropriation of a selfie she posted on instagram by Richard Prince:

In McNatt v. Prince et al, [1:16-cv-08896-SHS] filed in the Southern District of New York on November 16, 2016, McNatt complained about the reproduction of his photograph with a instragram-style border:

It hard to imagine that using almost an entire image and “framing” it with a few comments and graphics is “transformative,” and we will have to wait to see what the courts say. The Morris and Salazar cases have been dismissed by stipulation, the Graham and McNatt are still pending.

One wonders what upsets these plaintiff’s more, the fact that virtually their entire work is appropriated by someone, or the fact that that someone sells these “transformations” for as much as $100,000!